“Trust me, I’m a lawyer.” (Popular T-shirt slogan)

South African property buyers and sellers will have been cheered by news that we are now officially the most affordable country in the world in which to buy a home. We’re only a nose ahead of the USA and Bahrain in this particular race, but it’s great to be a world leader in something so positive for a change. Have a look at BestBrokers’ analysis of house affordability in 62 countries here to see just how unaffordable property is in many other countries around the globe.

This all bodes well for the South African property market, so it’s perhaps a good time to remind sellers that it’s not just about getting a good price for your house. Equally important is ensuring that you choose the right conveyancer to attend to the transfer for you, with a recent High Court fight over a dishonest attorney’s theft sounding a stark warning in this regard.

An absconding conveyancer steals R4.25m

Having bought a house on auction for R4.1m, the buyer paid the auctioneer the required 5% deposit and the auctioneer’s commission. The auctioneer duly paid the deposit to the conveyancer nominated by the seller and the conveyancer, having not yet turned to the dark side, paid the deposit over to the seller. So far, so good.

The conveyancer then issued a pro forma invoice to the buyer for the balance of the purchase price and transfer costs, a total of R4.25m. The buyer duly paid that amount into the conveyancer’s bank account specified in the invoice.

Conveyancers are obliged to pay all such funds into a separate trust account for safekeeping, but in this case it emerged (after the buyer queried inordinate delays in the transfer process) that the bank account specified by the conveyancer in her invoice was not a trust account at all. Worse still, she had absconded with the funds.

A series of tussles followed, with the buyer demanding the house be transferred to him because he had paid in full, and the seller countering that they had cancelled the sale because the buyer didn’t “secure” payment of the balance of the purchase price by paying it into a trust account.

The seller learns a hard lesson

The High Court, called upon to sort out who must ultimately bear the loss, held that by paying the conveyancer per her invoice, the buyer had done everything required of him by the conditions of sale and was entitled to transfer. It was not the buyer’s obligation to ensure that he was paying into a trust account and to monitor its safekeeping there until transfer. Rather, it was the conveyancer’s obligation to secure the funds in her trust account until transfer.

The end result is that the seller must now transfer the property to the buyer and try to recover his losses elsewhere. He can sue the conveyancer (not a hopeful prospect) and as a last resort he can lodge a claim with the Legal Practitioners Fidelity Fund (LPFF). He’ll be wishing he’d avoided all that cost, delay and risk by choosing a more trustworthy conveyancer in the first place.

(As a side note, the conveyancer has been suspended from practice and her firm placed under curatorship – she blames her total trust account shortfall of at least R8m on a dishonest bookkeeper.)

Remember: as seller it’s you who gets to choose the conveyancer, so choose wisely! And as always, don’t sign anything until we’ve checked it all out for you.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“The legal principles, as I understand them, do not confer on me the powers of Father Christmas. I cannot rescue the un-rescuable.” (Quoted in the judgment below)

We all want loyal, competent staff who remain motivated to stay with us in the long term, but the reality is that a degree of employee churn is always inevitable.

Imagine then this scenario – a key employee (someone senior, a specialist, or perhaps even a partner or director) is fired or leaves you. They take with them intimate knowledge of your business. They know all your trade secrets, your pricing processes, your marketing strategies, and all your trade connections. Plus, they’ve built up client relationships and credibility in your industry while employed by you.

If they now decide to start up their own business in opposition to you, or if they take their insider knowledge to your competitors, you have a real problem.

That’s why it’s essential to consider, right up front when you’re hiring someone and drawing up their employment contract, whether you need to protect your business from this sort of unfair competition. That’s where the tried-and-tested restraint of trade clause comes into play. It’s as easy as including one in your employment contract, and making sure that your new hire is fully on board with it. Or is it?

The basic requirements for legal validity

As a starting point, our courts are cautious about curbing anyone’s constitutional right to be economically active and to earn a living.

So, while we are all generally held to the agreements we make, and while restraint clauses have long been recognised in our law as a legitimate way for businesses to protect their interests from unfair competition, our courts are unlikely to enforce restraints unless they are:

- Reasonable: You cannot impose an unreasonable restriction on your former employee’s freedom to trade or to work. Go too wide on time period, geographic area or scope, and your clause could be held wholly or partially void.

- Protective of a legitimate business interest: You must have a real commercial interest in imposing the restraint, you can’t use it just to block competition.

- Not contrary to public policy: There must be no other aspect of public policy weighing against the clause.

Each case will be judged on its own facts and merits, with the court balancing your rights against those of your former employee in a bid to ensure fairness to both of you.

As a starting point, make sure that your clause isn’t “void for vagueness”, or you could end up in the same position as the employer we discuss below.

Too vague to enforce, and no Father Christmas to the rescue

An employer, providing physiotherapy services to two major hospitals in the Umhlanga area of KwaZulu-Natal, employed a senior physiotherapist in January 2023. Eight months later she resigned.

The restraint of trade clause in her agreement was a particularly terse one. Headed “15. Trade Restriction”, it read simply: “2 year 8km restriction in event of termination / expiry of Contract.”

When the employer tried to enforce this clause, the High Court refused, pointing out that it was “lacking in substance” and contained no indication of:

- A definite commencement date for the two-year period

- What the “8 km restriction” referred to

- What exactly was restricted

- What interests it sought to protect

What’s more, it contained no mention of the two particular private hospitals which the ex-employee was not to practice at. The Court refused the employer’s request to “read in” more wording to the clause to remedy its vagueness and lack of detail, quoting from another High Court decision: “the legal principles, as I understand them, do not confer on me the powers of Father Christmas. I cannot rescue the un-rescuable.”

It also warned against the trend for smaller businesses to cut corners by going the “DIY contract” route: “SMME businesses are reluctant to seek advice from attorneys, and less so to employ attorneys to prepare important legal agreements. This pattern, fuelled undoubtedly by the rising cost of legal charges, often results in unforeseen circumstances by the time the matter reaches a litigious stage”.

That’s putting it mildly – defective restraint clauses like this one literally aren’t worth the paper they’re written on. A properly drawn clause is essential, and we’re here to help.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“Grandparents, like heroes, are as necessary to a child’s growth as vitamins.” (Quoted in the judgment below)

One of the greatest tragedies of family fall-outs will always be the effect they have on the children involved. A recent High Court fight over a granny’s attempts to have contact with her two grandchildren in the face of bitter opposition from their father confirms that what really counts is what’s best for the grandchildren.

A tragic death, and a family fight

Two boys, aged 9 and 13, are the innocent subjects of this legal wrangle. They live with their father in Makhanda.

Their mother, a professional nurse serving in the SANDF with the rank of captain, tragically died in a motor accident three years ago.

Their father, currently a High Court advocate, had met their mother while a member of the SANDF’s Special Forces Unit. They were never formally married but the two children were born of their union. He is described as a good father providing his boys with good care and a stable home and family life.

Their grandmother is widowed and a retired nurse and midwife. Her requests to the father for contact with her grandchildren were met with an obstinate refusal to even engage with her. His intense dislike for her – based, he said, on his late partner’s anger issues with her – was reiterated in his stance in the Children’s Court where he made it clear that he refused ever to talk to her.

The grandmother lives in the village of Herschel on a large plot, is in good physical and mental health, and says she is well able to look after for the children while in her care.

The Children’s Court, having received the reports and evidence of social workers (which spoke of a healthy relationship between mother and grandmother in contradiction to the father’s perception), granted access to the grandmother.

The father appealed this order to the High Court. While accepting that the father genuinely believed that he was acting in his children’s best interests, the higher court upheld the contact order, albeit in a more structured form than the original. The grandmother now has access by way of:

- Weekly telephonic/multimedia contact

- Monthly day visits with her in Makhanda

- Mid-year and year-end school holiday visits to her home in Herschel, for a week at a time, initially under the supervision of the Department of Social Development

The decisive consideration

The Children’s Act sets out in detail a wide variety of factors to be considered by a court in deciding any application for access (referred to as “contact” in the Act). But as the Court here pointed out, the decisive consideration is always going to be the best interests of the child.

Every case will be unique, but one highly relevant factor that our courts will have regard to is “the need for the child to remain in the care of the parent, family, and extended family and to maintain the connection with his family, extended family, culture and tradition”.

Let’s close with this particularly apt observation from the Court (emphasis supplied): “Usually, it is in the best interests of a child to maintain a close relationship with his grandparents”.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of bandages and adhesive tape.” (Groucho Marx)

It’s a perennial topic of dispute in our courts. A couple lives together, sharing the same roof and everything else in perfect happiness and harmony.

Until it all goes south. Then the gloves come off and, particularly if our erstwhile couple end up dragging each other through the courts, everyone takes a beating. Bloodied, battered and bandaged, they’re going to wish they’d implemented Groucho’s “ounce of prevention” in the first place.

We’ll explain how to keep things amicable. But before we do, let’s consider the case of the life partner who failed to persuade a court to give him a cut of his ex-partner’s house.

Trying to prove a “universal partnership”

Bearing in mind that our law recognises no such concept as “common law marriage” (a pervasive and dangerous myth that just won’t go away), many an ex-life partner has fallen back on trying to prove that the couple had formed a “universal partnership”. Depending on the type and form of the partnership they claim existed, that would give them a cut of the assets of their relationship. But it isn’t easy to prove.

The facts in a recent Limpopo High Court fight illustrate this point. A couple in a romantic relationship had lived in the woman’s house with her daughter. Each of them contributed equally towards household expenses. They decided to extend the house, and the man contributed R416k out of his pension payout for this purpose.

When their relationship broke down after five years, the man tried to convince the Court that a universal partnership had been formed between them, and he asked for a liquidator to be appointed to divide the partnership’s assets equally between the partners.

The Court’s thorough analysis of the law relating to universal partnerships (there are actually two types, both with fancy Latin names) will be of major interest to lawyers. But what really matters most to you on a practical level is that:

- The onus is on you to prove that a partnership existed, and its terms.

- You must prove that you agreed to pool your assets in order to make a profit.

- A universal partnership needn’t be agreed to in writing – it can be formed verbally, by consent, or by the conduct of the parties. That requires inferences to be drawn so it’s a recipe for misunderstanding and dispute. Without a written agreement it’s never easy to prove and our case law is littered with failed attempts.

- Perhaps the most pertinent factor of all is this comment by the Court (emphasis added): “The mere fact that parties cohabitate does not entitle them to a proportionate share of the other party’s estate.”

In the end, the applicant failed to prove that the relationship had been anything more than cohabitation, so he leaves with nothing (other than, of course, a large legal bill).

An ounce of prevention…

All that litigation and unhappiness could have been prevented had the parties, when they first decided to live together, entered into a cohabitation agreement.

Don’t make the same mistake, and be sure to draw up a document covering, at the very least, the following aspects of your relationship as they apply to you:

- When your relationship began or when the agreement takes effect.

- List who owns what both before and during cohabitation (furniture, vehicles, investments and so on).

- Who is responsible for which debts.

- Who owns (or rents) your house, who will pay the bond instalments if any, who will pay for what upkeep, who will pay for any major extensions or repairs, and so on.

- Who will pay what in ongoing contributions to shared living expenses.

- Will you use joint bank accounts and, if so, how will you manage them?

- Will you run your own businesses, a joint business, or no business at all? What will you each contribute, what will you each take out, how will you manage the business/es?

- Who will be responsible for the children’s financial support, schooling etc?

- If your relationship ends:

- How will you terminate it?

- Who will get which assets?

- Who will be responsible for which debts?

- How will you terminate any business relationship you have?

- Will either of you be entitled to ongoing spousal maintenance?

- What happens to your children, to their financial support, and to your parental duties and rights of contact?

- Think of adding a dispute resolution clause to kick in if you can’t agree on anything.

- Anything else? Your circumstances are going to be unique to the two of you, so brainstorm for anything else (who gets the pets, for example) that you’d like to record or agree on at this stage.

Herein lies the rub

Setting out an agreement doesn’t mean you’re planning for failure! In fact, you’re increasing your chances of success. Break-ups are a fact of life, and even if you do grow old and wrinkly together, your cohabitation agreement will still come into its own when one of you dies.

On that note, don’t forget to make or update your will (“Last Will and Testament”) at the same time. Both documents are essential, and the two must be compatible with each other, so make a big note to review/update both together.

Bottom line: you and your life partner should have a cohabitation agreement as well as wills. We’ll help you put all that together.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“Look before you leap.” (Wise old proverb)Imagine sealing the deal on your dream property, only to wake up at 3 a.m. beset by sudden doubts. Thoughts like “Can we really afford it?” or “How on earth could we have fallen in love with that old dump?” haunt you. You may have a strong urge to back out – but tread very carefully here. Trying to cancel the sale without sound legal grounds will be a big and costly mistake. A recent High Court case provides the perfect example.

The R135m house and the “defects” that weren’t

Our buyer put in a R135m offer for a luxury three-storey house in Sandhurst. The cancellation clause in his offer document read (emphasis added): “The Purchaser at his own expense will conduct an inspection of the home within (14) fourteen days of acceptance of the offer. Should there be structural defects or defects that are unacceptable to the Purchaser then the Purchaser can at his discretion elect to cancel this agreement.” The seller accepted the offer with that cancellation clause – deal done. But then, eight days later, the buyer tried to escape the sale with this email from his attorney: “Unfortunately after conducting due diligence, the purchaser hereby elects to cancel the agreement… Good luck with the sale.” The buyer’s remorse in this case turned out to be monetary – he had, he said, overpaid for the property. He then put in a new offer for R100m. That was a loss the seller wasn’t going to accept, so daggers were drawn, and the fight was on. The seller hotly denied that the buyer had any right to cancel the sale agreement, and off they went to the High Court. The buyer said that he had “unfettered discretion” to decide whether or not there were defects, and he refused to give the seller any details of them. Only in his court papers did he provide more information, claiming to have noticed cracks on the walls during an inspection. The rest of his “concerns” related to his personal preferences for the house – wanting new paving, widening the driveway, remodelling the kitchen, installing an elevator and the like.Subjective belief in a defect isn’t enough

The Court had no hesitation in holding that the buyer had not been entitled to withdraw from the sale “based on any minor ‘imperfection’ in the property, because it does not fulfil his personal needs – at his sole discretion and without proof.” He had failed, as required by law, to exercise his discretion reasonably and to prove the existence of a defect objectively (i.e., based on facts, not personal belief) rather than subjectively (i.e., based on the buyer’s personal opinions or interpretations). His subjective interpretation was irrelevant. The bottom line: the seller had rightly rejected the buyer’s cancellation, and the buyer remains bound to the sale. To rub salt into his wounds he must now also pay costs on the attorney and client scale – that’s going to be expensive!What then is a “defect”?

Per the Court, the ordinary meaning of a defect is (emphasis supplied): “an ‘abnormal quality or attribute’ of the property sold that ‘destroys or substantially impairs’ its ‘utility or effectiveness’ for the purpose for which it is generally used or unfit for the special purpose for which it was intended to be used by the purchaser.” Personal preferences like elevators and revamped kitchens don’t count, and a wall crack justifying a R35m price reduction can’t be superficial!Look before you leap!

Some final thoughts for property buyers:-

- Don’t rush (or be rushed) into buying anything. Take your time, and make sure this really is the property for you and that you can afford it.

-

- Check the house thoroughly for any potential problems and consider commissioning an independent home inspection to look for any defects that might not be immediately obvious (damp for example). If you are worried about anything in particular, bring in the experts or insist on expert reports from the seller.

-

- Last (but certainly not least) don’t sign anything without asking us to review all the paperwork for you first!

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“My word is my bond.” (Once the motto of 16th-century merchants, adopted by ’90s hip-hop artists, and now tossed around by duelling politicians)Many people are unaware that there are just a few types of agreement that are valid only if recorded in writing and signed – most notably contracts for the sale, exchange, or donation of land or of any “interest in land”, ante-nuptial contracts (ANCs), and deeds of suretyship. Outside of those exceptions, all verbal agreements are as valid and enforceable as written ones. Your word really is your bond! So be careful what you agree to verbally – and stick to written agreements whenever there’s a lot at stake. A recent High Court judgment provides a great practical example of those principles at work.

When friends fall out

It’s 2009, and the MD of a long-established Cape Town freight operation is doing business with another business owner. Their relationship develops from a strictly business one into a personal, “best friend” one. By 2012, they have agreed verbally that the friend will move to Johannesburg to establish a branch of the freight company there as a new director. Believing that he will now be given a 5% share in the company and be appointed as a director, the friend pays the company R1m to cover the new branch’s start-up funding. But when he asks for his shares, the MD refuses, denying there was ever any agreement to give him equity and telling him that the R1m was just an “at-risk investment”. The refusal to give him shares, says the friend, is a repudiation (renunciation) of the oral agreement, and he demands that the company now repay his R1m. The company, through its MD, refuses – “I’ll see you in court,” he says. In the latest (2025) round of litigation, the Court, without a written agreement before it, has to analyse a litany of contradictory evidence to try and work out what exactly had been verbally agreed by the two ex-friends.Offer someone a carrot and you’ll have to give it to them

The Court was unimpressed with the MD’s version that his friend’s R1m payment was an “at-risk investment” rather than the agreed purchase price of a 5% shareholding. A major factor in that decision was clearly the director’s 2013 email to his friend which included this: “…I have committed to sell you equity…”, reinforced by his evidence that he only changed his mind about parting with shares in 2014. The nail in the MD’s coffin was no doubt his admission that that he had held out the prospect of his friend becoming an equity partner as “a carrot”. His friend accepted that offer, their oral agreement became binding, and the company must repay the friend his R1m plus interest and costs. Offer someone a carrot, and our law will hold you to deliver it!“The bluntest pencil is better than the sharpest memory”

While it seems justice has been done, both the falling out and the court case could have been avoided altogether. Had the MD and his friend thought the whole thing through properly back in 2012 and asked a lawyer to draw up a proper written agreement for them, it’s highly unlikely that they would, in 2025, still be fighting their way through the courts. Who knows, they might never have come to blows at all and could still be BFFs! Don’t rely on a “handshake” agreement, even with the best of friends. When the stakes are high, let us help you put it in writing – clearly, enforceably, and with a minimum of fuss.Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

It’s vital for both employers and employees to understand the practical and legal differences between permanent and fixed term employment arrangements.

What is a fixed term contract?

A fixed term contract is a temporary employment arrangement with a specified start date and an agreed end date. This could be a fixed end date or a reference to a specified task or project reaching completion, or to a specified event. Importantly, you must be able to prove that your employee agreed to the end date.

A standard contract of employment, by contrast, is for an unlimited period and ends only when your employee resigns, or reaches retirement age, or is lawfully dismissed or retrenched by you.

Any employer tempted to misuse a fixed term contract in order to dodge the many legal protections given to a full-time employee should think twice – our courts do not look kindly on attempts to prejudice employees by disguising the true nature of an employment relationship.

The basic requirements

The contract (and any renewal contracts) must be in writing and must state the reasons justifying the stated fixed term.

The protections

The Labour Relations Act (LRA) provides a range of protections to fixed term employees. Let’s address them under two main headings.

Firstly, the “reasonable expectation of renewal” protection that applies to everyone

Simply put, you could face an unfair dismissal claim (with all that that entails) if you give the employee reason to believe that the contract will be renewed or converted to full-time employment.

That’s because – and this applies to all fixed term contracts in that none of the exclusions listed below apply here – the LRA says the termination of a fixed term contract is seen as a “dismissal” if:

- The employee “reasonably expected” you to either renew the fixed term contract on the same or similar terms, or to convert the contract into indefinite employment (again, on the same or similar terms), and you didn’t do so.

Anything could land you in hot water here, with particular risk areas being things like continual renewal of fixed term contracts without justification, verbal or implied reassurances of renewal, a workplace culture of renewing contracts etc. To be on the safe side, consider giving your employee specific written notice of non-renewal in good time. Every scenario will be different here, so in some instances you may be advised that multiple contract renewals are justified, in others that they aren’t – specific legal advice is essential, and the bottom line is that professionally drawn contracts and clear communication are critical.

Secondly, other protections that apply only to certain employees

These additional protections do not apply in any of these exceptions:

- The employee earns more than the earnings threshold set by the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (currently R261,748.45 per year or R21,812.37 per month).

- You employ less than 10 employees.

- You employ less than 50 employees in a business that is less than two years old (and that hasn’t been formed by dividing or dissolving an existing business).

- The fixed term contract is permitted “by any statute, sectoral determination or collective agreement.”

The three-month limit, and the need for justification

You can only use a fixed term contract (or successive contracts) for over three months if:

- The work involved is of limited or definite duration, or

- You are able to prove a justifiable reason for fixing the contract’s term, with the LRA specifically mentioning situations such as:

- Covering another employee’s absence (on maternity leave perhaps)

- Addressing a temporary increase in work not expected to last over 12 months

- Providing work experience to students and new graduates

- Specific projects of limited or defined duration

- Seasonal work

- Positions funded externally for a limited period

- An employee who has reached retirement age

This is not an exhaustive list so you may well have other justifiable reasons, such as perhaps needing to establish the viability of a new venture, a new branch, or a new position before committing to long-term employment.

Watch out here! If you employ someone on a fixed term contract for more than three months without complying with the above, the contract is automatically deemed to be a full employment contract of unlimited duration.

Other things to watch

- Equal treatment after three months: Even if you have justification for exceeding the three-month limit, you must then treat the employee no less favourably than a permanent employee in the same position, unless again you have justification for different treatment.

- Right to apply for vacancies: Fixed term employees must have the same access to apply for vacancies as permanent employees.

- Retrenchment pay if a project exceeds 24 months: Any project-specific fixed term employee who is employed for over 24 months must, when the contract ends, be paid a week’s remuneration for every completed year of the contract or offered other employment (with you or another employer) on the same or similar terms.

A properly drawn employment agreement that both protects your interests and complies with the law is essential – and we’re standing by to help you.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“A body corporate’s lot is not an easy one.” (With apologies to Gilbert and Sullivan)

One of a body corporate’s core functions is to collect current and outstanding levies. When a section owner becomes uncooperative, recovery can turn into a difficult, costly and lengthy process. Good news for trustees is that it just became a little easier after a recent High Court ruling which authorised a body corporate to cut off an owner’s electricity for failure to pay his consumption charges.

“The pandemic made me do it”

An owner of an apartment in an 86-unit sectional title scheme in Sandton fell into arrears in 2021. Two years later he owed a total of R107,940 … R16,610 of which was for unpaid electricity charges.

The body corporate sued him, asking the High Court not only for a monetary judgment but also for authority to cut off his electricity supply pending payment. It pointed out that the scheme pays Eskom for its electricity and then invoices unit owners for consumption recorded on their individual meters. That put all owners at risk of being cut off by Eskom if the body corporate was unable to pay its monthly account.

The owner admitted owing the amount claimed, which he said had resulted from a loss of income as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. He offered to pay off the arrears in instalments of R8,000 p.m. and opposed the application to cut his power on constitutional grounds.

The Court authorised the body corporate to disconnect the owner’s electricity supply until he pays the portion of the arrears relating to electricity.

How the body corporate won – follow this recipe

As the Court put it: “There is tension between competing interests in this matter: the right of the Body Corporate to be reimbursed for payments made on behalf of the unit owners and the right of the owner to be supplied electricity.”

In other words, it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that the body corporate would automatically succeed here. So don’t just assume that you now have carte blanche to force payment of arrears by cutting off electricity.

Rather follow the recipe for success that worked for this body corporate:

- Don’t act arbitrarily: The owner relied partially on constitutional protection against “arbitrary deprivation of property”, but the body corporate was able to counter that it wasn’t acting arbitrarily at all. On the contrary, it was asking the Court for permission to disconnect. Arbitrary disconnection not authorised by a court order will in any event put you in the wrong and risk the owner obtaining a “spoliation” order. That would force you to switch the power back on immediately without any investigation into the rights and wrongs of the matter.

- Give proper notice of disconnection: The body corporate had ensured procedural fairness by giving the owner proper notice which spelt out the consequences of non-payment of his levies (including application for a court order to disconnect electricity).

- Make sure all your resolutions are in order: The Court analysed the various resolutions passed by the body corporate in respect of imposition of levies and collection of arrears before confirming that they were enforceable against the owner.

- Proving “prior agreement”: The owner argued that he had never agreed to disconnection on non-payment, but the Court held that there was indeed a tacit (inferred) agreement by him to repay the body corporate for its payments to Eskom, and that he was bound to the scheme’s rules and regulations regarding enforcement. You need to have all your paperwork in order to achieve the same result.

- Balancing competing interests: You will need to persuade the court that your scheme’s interests trump those of the owner. In this case, the scheme’s financial stability was put at risk, exposing all owners to the risk of disconnection – while the defaulting owner continued to benefit from electricity at the expense of the other owners.

An important caveat

Although the body corporate had applied for an order to disconnect electricity until the full judgment amount of almost R108k had been paid in full (i.e. including the levy portion of R91k), the Court limited its disconnection authorisation to recovery of only the arrears for electricity consumption (plus interest). It gave no reasons in its judgment for not linking reconnection to payment of the full R108k – but its comment that the electricity non-payment was the most prejudicial to the scheme suggests that it will always be safest to assume that your rights to disconnect electricity may be similarly limited.

Whether you’re a body corporate or a sectional title owner, navigating situations like this requires carefully ticking all the legal boxes. You know who to call!

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“Good in parts” (Like the curate’s egg)

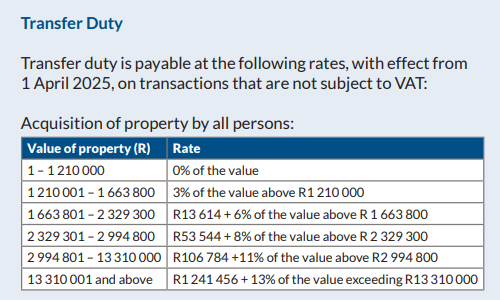

Transfer duty threshold increased by 10%

You pay no transfer duty if the property you are buying sells for less than the set threshold. The threshold wasn’t increased last year, so this year’s proposed 10% increase from R1,100,000 to R1,210,000 (from 1 April) is a welcome adjustment for inflation.

With all the brackets adjusted upwards by 10% as per the table below, properties at every level become that much more affordable to buyers, and by extension sellers will also benefit.

Source: SARS

The ongoing VAT increase saga

The proposal to increase VAT from 15% to 16% over two years, with a 0.5% hike planned to take effect on 1 May 2025 and the other 0.5% on 1 April 2026, has met with fierce resistance from business, consumers and trade unions – and from the opposition benches in parliament.

As to when we can expect clarity on whether government will be able to muster enough support in parliament to convert this and its other proposals into law, we are sailing in uncharted waters and only time will tell. Hold thumbs!

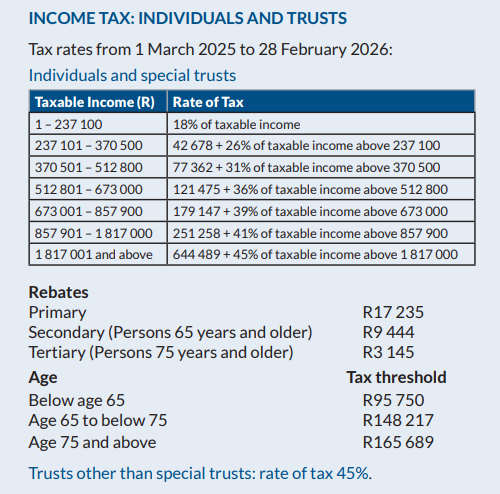

The unchanged tax tables, and no new taxes

Individual taxpayers: Your tax rates (and the associated rebates and medical tax credits) are unchanged, so we can at least be thankful that there were none of the major increases that had been hinted at.

What will hurt us is that for the second consecutive year there is no inflation adjustment to the tax brackets, which means that “fiscal drag” (also referred to as “bracket creep”) will leave you paying more tax if you receive an increase – particularly if it pushes you into a higher tax bracket.

Trusts: Special trusts are by and large taxed as individuals, but other trusts are taxed at a flat rate of 45% – again unchanged from last year.

Source: SARS

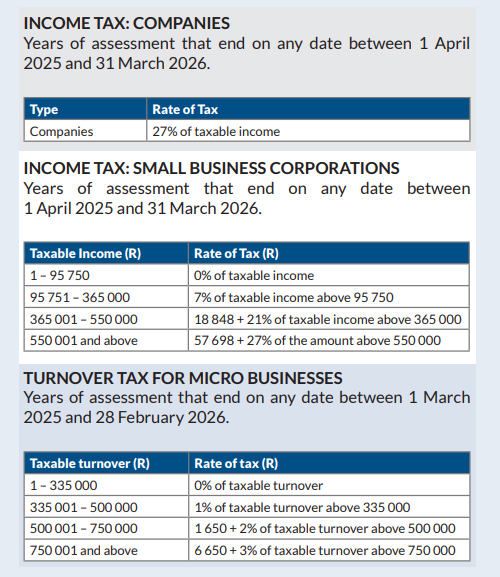

Corporate and other taxes: Corporate and dividend tax rates, capital gains taxes, donations tax and estate duty all remain unchanged. With all the pre-Budget speculation about possible increases in these taxes, perhaps coupled with a new wealth tax and/or new taxes to fund the NHI (National Health Insurance), this is good news.

Source: SARS

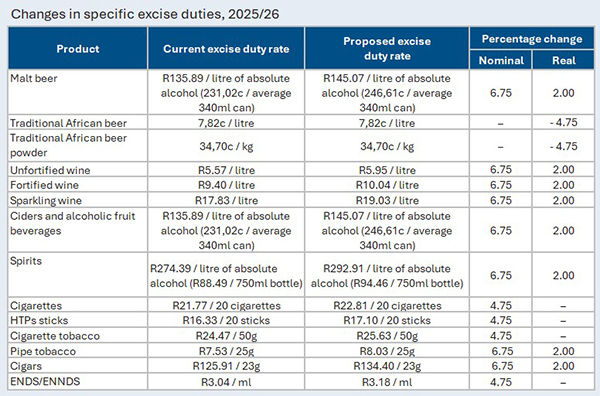

“Sin taxes” up – the details

Increases in sin taxes were mostly above inflation at 6.75% for alcohol and 4.75% – 6.75% for tobacco products – see the table below for full details.

Source: National Treasury

How much will you be paying in income tax, petrol and sin taxes? Use Fin 24’s four-step Budget Calculator here to find out.

Note: There is (at time of writing) uncertainty as to whether or not the Minister will proceed with his proposed tax changes – even if he fails to garner sufficient political support to ultimately ensure their adoption by parliament. If he does proceed, it’s equally unclear how long they will be valid for. Regardless, expect a lot of political manoeuvring and perhaps some major changes in the weeks ahead!

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews

“All that glisters is not gold” (William Shakespeare in Merchant of Venice)

Buying or selling a home could be one of the most important financial decisions you’ll ever make. It’s an exciting time – but don’t lose sight of the need to tread with care.

A key player in the process is likely to be an estate agent, to whom you will be entrusting one of your most significant assets. It goes without saying that you need to choose someone both competent and trustworthy.

Fool’s gold?

Be particularly careful here, because not everyone who claims to be an estate agent is genuine – and you will be in for a world of pain if you inadvertently trust your property transaction, and your money, to a charlatan. A fake agent may be actively dishonest or merely incompetent, but (in the way of all con artists) is probably first and foremost a persuasive and convincing liar. Lots of “glister”, but absolutely no gold!

Quite apart from the competency angle, just Google a phrase like “fake estate agent sentenced” to get an idea of how much full-on “bogus agent” fraud there is.

Let’s have a look at one recent case.

The Hawks swoop, and a fake agent gets 23 years

A fraudster operating in Bloemfontein and pretending to be an estate agent conned his victim into signing a sale agreement and paying him R100,000 for a house she’d set her heart on. Too late, she discovered that the “agent” was neither registered as such nor entitled to sell the house.

The matter was handed over to the Hawks, and the fake agent is currently serving an effective 23 years’ direct imprisonment. Justice served, and let’s hope the victim, to whom R100,000 is clearly a substantial sum, is also able to recover her hard-earned money from the fraudster.

A timely warning

A timely warning from the PPRA (Property Practitioners Regulatory Authority) in February confirms that, quite apart from the risk of fraud, it’s crucial for your protection to ensure that the agent you decide to work with is properly registered with the PPRA and holds a valid Fidelity Fund Certificate (FFC).

Why is PPRA registration important?

The PPRA is the official body that oversees estate agents and other property practitioners. Registration with the PPRA ensures that:

- The agent operates legally and is subject to the PPRA’s Code of Conduct.

- The agent has met the necessary training and compliance standards.

- You can claim against the Property Practitioners Fidelity Fund for any theft of trust money by an agent with a valid FFC.

Four checks before you engage an agent

Before giving a mandate to an estate agent or agency, it’s important to check that they are legit. You can do this by:

- Confirming their registration and FFC: Ask for proof that the agent and the firm are registered with the PPRA. Request copies of their FFCs and verify their validity for the current year by phoning the PPRA on 087 285 3222.

- Verifying supervision for candidates: If dealing with a candidate property practitioner, confirm that they are working under the supervision of a fully registered agent.

- Checking their trust account: If you pay money to an agent (a deposit perhaps), make sure the firm is registered with the PPRA and has an active trust account held at a registered South African bank. The funds should be deposited into this trust account and not into the agent’s personal or business account.

- Asking us! We can help you with all these checks – and if you aren’t sure who to use, we’ll point you in the right direction.

Disclaimer: The information provided herein should not be used or relied on as professional advice. No liability can be accepted for any errors or omissions nor for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon any information herein. Always contact us for specific and detailed advice.

© LawDotNews